In 1890, "a plucky young Texan" paddled his canoe from New York City to Astoria, Oregon. A staff correspondent for New York's Mail and Express, R. Elbert Rappleye's odyssey spanned 6,280 miles and was undoubtedly a first. What's crazy to consider is that 130 years on, there isn't a West Coast to East solo, continuous canoe expedition on record. It feels awe-inspiring to traverse the nation by canoe, to span the country with a journalistic eye, and with a bit of luck and success, to pull off a reverse record.

Having paddled and portaged up the Columbia, Snake, and Clark Fork Rivers, I’m currently in North Dakota at Tobacco Gardens Resort & Marina on Lake Sakakawea (on my second cross-country shot). I spent months to plot and plan out the unique cross-country route. It’s amazing, but without knowing about Mr. Rappleye until now, from the rivers and lakes of Idaho and Montana to Lake Chautauqua, Lake Erie, the Erie Canal, the Hudson, and even my final destination of New York City, I’ll be casting my eyes and scribbling in my notebook, from water level, along and upon a number of similar vistas and waterways.

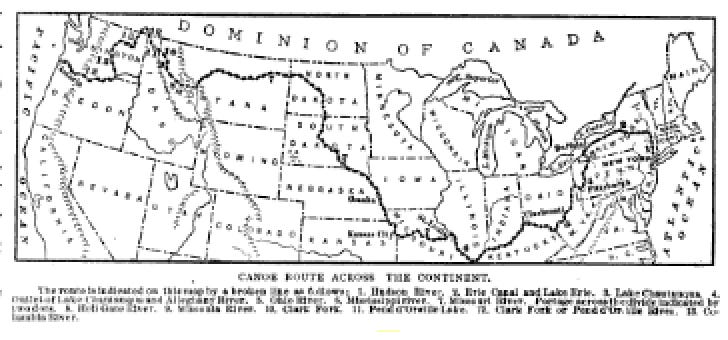

Mr. Rappleye’s cross-country canoe route, from East Coast to West, 1890.

Mr. Moore’s cross-country canoe route, from West Coast to East, 2020-2021.

If you’d like to follow my journey, you can check in and see exactly where I’m at with this link: https://sharelocation.app/QftM2xU

Thanks to Norman Miller for the information on R. Elbert Rappleye, and for chronicling all long-distance paddlers to touch the Missouri – and beyond.

Here is the original article about Rappleye’s voyage from 1891:

R. ELBERT RAPPLEYE, a plucky young Texan educated in New York, has just won the glory of making one of the longest trips on record in a small boat. He crossed the continent from New York to Astoria, Oregon, on the Pacific, a distance, over the necessarily circuitous route of more than 6,200 miles. The canoeist had necessarily to carry his light, but tough, paper craft, Only twelve miles during his protracted voyage. The length of the land voyage was, however, increased by the unnecessary transfer of his boat to Lake Chautauqua and by encountering ice in the Rocky mountains. He paddled down 150 miles of the Missoula river, in Montana, that, the settlers said, never had been successfully navigated before.

The canoeist launched his little boat from the Jersey City Yacht Club on April 10, 1890, and started up the Hudson river. He paddled from the Hudson through the Erie canal and into Lake Erie. It was his intention originally to go from Lake Erie by way of the Miami canal, which connects the lake with the Ohio River; but the citizens of Jamestown, N.Y., prevailed upon him to leave Lake Erie at the nearest point to Chautauqua lake, and transported him to Mayville, whence he was escorted to Jamestown by the Chadaukoin Canoe Club.

Everywhere he touched he was welcomed with enthusiasm and entertained and feasted. Word of his coming was flashed over the wires from town to town, and there were always many to meet him at the landing place. He passed through North and South Dakota, and, on August 30th, visited the camp of Sitting Bull. He reached the divide in the Rocky Mountains in October. Here he was the first necessary portage of the voyage. The battered canoe on which were written the names of hundreds who had helped to welcome the voyager at points along his course, was slid into the Hell Gate river at Missoula, in the presence of a thousand citizens, who cheered its departure for the western coast. The canoeist took a passenger at Missoula, the first in his long course, who was invaluable to him as a guide. He was Frank Whittaker, an old Leadville miner, who left him at Paradise, Montana, where he joined a survey party. He had the company of David W. Low, a young man and enthusiastic canoeist of Missoula, from the time he parted company with his first passenger until he reached Astoria.

A longer carry over the divide than would have been necessary in summer had to be made because of the ice in the mountain streams. To make a short portage he would have had to remain all winter in the mountains and start down the Hell Gate when nature broke the ice barriers in the spring. The voyager was not any too soon in reaching Missoula, as the water froze in his wake. When he came out of his tent in the morning to make breakfast, the coffee and water in his tin bucket was solid. Much of the rest of the journey was through snow storms, for the winter had set in earnest. From the Missoula Mr. Rappleye paddled into the Clark fork of the Columbia, and cruised thence into the Pend d’Oreille lake, in northern Idaho. Sliding down the outlet of the lake, the Pend d’Oreille river, the paddler floated into the Columbia river and down to Astoria, where he was joyously greeted by the expectant citizens, who had been reading about his journey for months. He mingled some of the Atlantic that he had taken with him with the Pacific.

Other canoeists who have made celebrated voyages in paper boats are Bishop and McGregor. The former went from Pittsburgh to New Orleans, a distance of 2,600 miles, in 1875; wrote a book about the trip, and had his canoe, the Maria Therese, exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in 1876. McGregor won fame by his cruises on the Baltic, the Jordan, the Nile and the lakes and rivers of Europe.

Mr. Rappleye has called attention, by his trip, to a geographical fact not popularly known – that, barring a few miles, there is an all water route from the Atlantic to the Pacific. He has probably seen more of the United States, and paid less for the privilege, than any man who has ever crossed the continent.

We have the newspaper reports he sent back. His sister Mae saved them all. He met with Siting Bull and was given a knife sheath as a gift! Elbert Rappleye Brewster.

Thank you! Elbert is my great grandfather, my father’s name sake. I am deeply touched.